Level design and environment design are two separate aspects when

a game is in development, although are not necessarily held as completely separate

elements, as generally the jobs are interchangeable with an individual in the

industry. As I touched upon last year, environment design refers to the

aesthetics of the assets which are places in the environment – an environment

artist will model, texture and on occasion light an environment to create a

visually appealing level. Level design refers to the assembly of said

environments. In general, a level designer will design gameplay elements, as well

as create scripted events and test gameplay – basically, the interaction with

the environment artist’s creations. Their job is to create a level, environment

or world in which a player can interact with and not get bored – and depending

on the game type, avoid replication the mundane tasks of an individual’s everyday

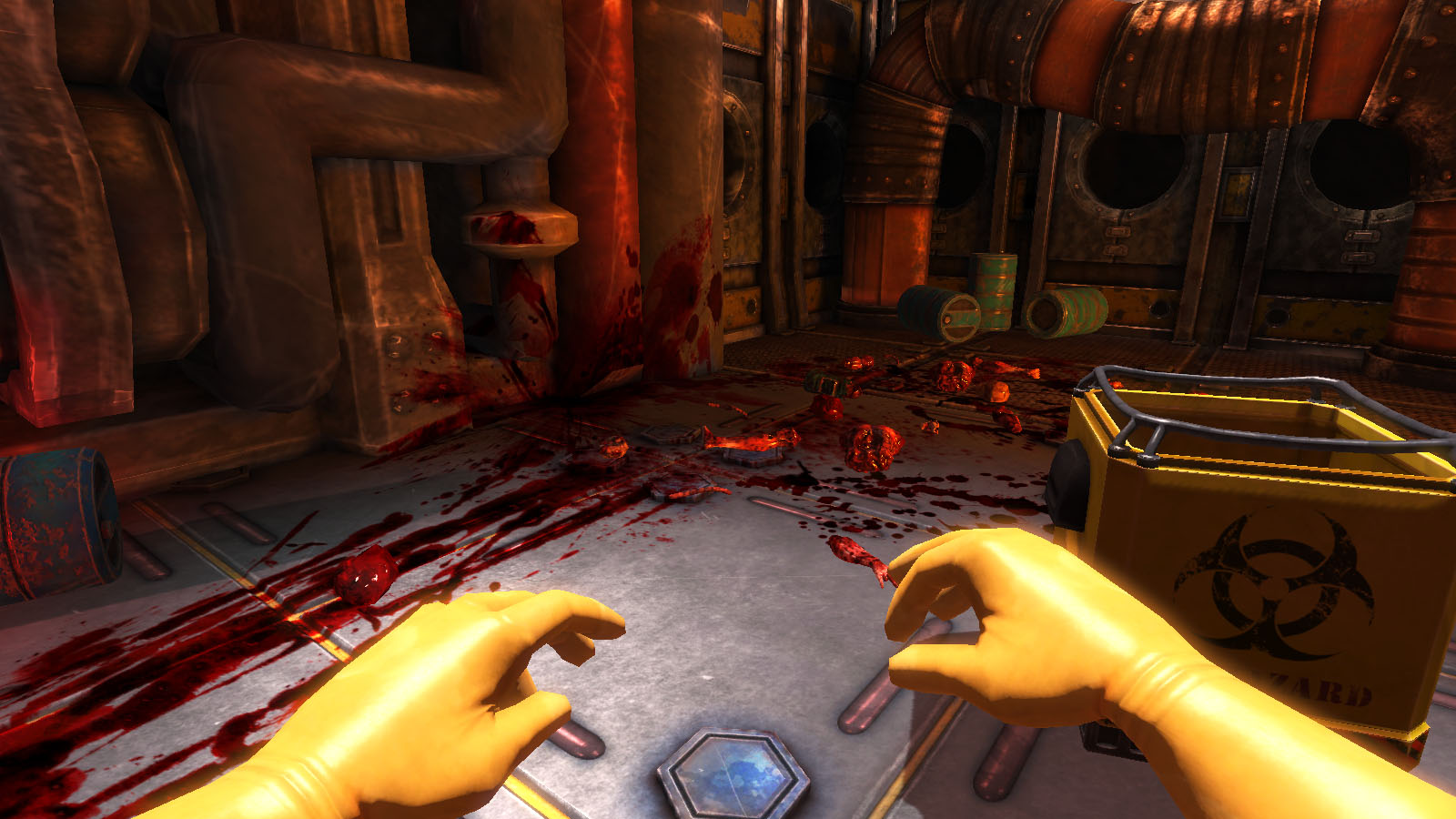

life. Then again this is really just a suggestion, as if people can find a game

based around mopping and cleaning interesting as long as its blood, guts and in

space then who knows.

|

| Viscera Cleanup Detail - The space-station janitor simulator |

Generally, what can be classed as good level design can be categorized

into fundamental “rules” as it were. Starting with the navigation through a

level – this being one of the core interactions a player has with the

environment they have been presented. Crap layout can hide visual cues as to

where a player has to go – in most cases this comes in the form of a light

source, corridors, colour coded areas

such as in mirrors edge, blocked off “you can only go this way” sections, or

the way in which the scary monster just went. Good navigation creates a good flow

within a games level, with consistent themes throughout a game allowing a more

instinctual interaction from a player.

Another suggested “rule” of game level design is the use of environment to tell

the story, relying on just the right amount of visual cues to allow the player

to immerse themselves and uncover the story for themselves without it being

shoved down their throat. Narrative aspects of a level can be done in three

ways, explicit – referring to text or speech, implicit – referring to the

environmental cues, such as in Bioshock or Fallout 3’s use of notes, and

emergent – this being narrated by the player as they travel through the level.

One of the more optional aspects of good level design is the players’

interaction with quests/objectives, and how they are to be fulfilled. In the Elder

scrolls series it is a general running design that the character gets to choose

their morality, and how certain quests can be ended – this affecting the

environment around them in multiple ways. This leads into gameplay – quests and

locations of interest should be distinct in their marking, with the option of

how a location is interacted with being determined by the player. Doing so

allows a game to steer away from repetition, giving some more variety in doing

tasks and interaction where the player feels as though they are writing their

own story.

The difficulty of a game is a sign of good level design – although maybe not one of the most important ones. I personally know I appreciate it when a game allows myself to select what difficulty I want to approach a game in, allowing me to get the enjoyment I want without unnecessary rage quitting – AKA: Dante’s Inferno. Adjusting the levels of enemies, difficulty of environments and the levelling curve via the adjustment of the difficulty can create a more rewarding experience with a personal feel.

The difficulty of a game is a sign of good level design – although maybe not one of the most important ones. I personally know I appreciate it when a game allows myself to select what difficulty I want to approach a game in, allowing me to get the enjoyment I want without unnecessary rage quitting – AKA: Dante’s Inferno. Adjusting the levels of enemies, difficulty of environments and the levelling curve via the adjustment of the difficulty can create a more rewarding experience with a personal feel.

Level design, in reality, wants to create an easy-to-play but not

in your face, personalised, interesting and all round awesome experience for a

player, showing off the visual environmental designs to their fullest whilst

creating flowing, logical interaction with them which both strays from everyday

life, but maintains balance in the real world with its understantability and

interaction with an individual’s awareness and intuition. They should create

emotive responses which fuel gameplay, with levels which highlight specific

mechanics within a game.